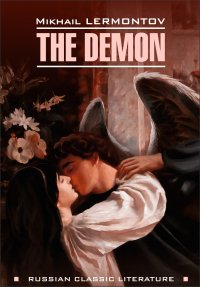

Демон

Книга для чтения на английском языке

Покупка

Тематика:

Английский язык

Издательство:

КАРО

Автор:

Лермонтов Михаил Юрьевич

Год издания: 2020

Кол-во страниц: 192

Возрастное ограничение: 16+

Дополнительно

Вид издания:

Художественная литература

Уровень образования:

Дополнительное образование

ISBN: 978-5-9925-1427-8

Артикул: 749989.02.99

Предлагаем вниманию читателей сборник поэтических произведений Михаила Юрьевича Лермонтова (1814-1841) в переводе на английский язык. В книгу вошли знаменитые поэмы «Демон» (1838), «Мцыри»(1839), «Песня про царя Ивана Васильевича, молодого опричника и удалого купца Калашникова» (1837) и избранные стихотворения 1831-1841 годов. Романтические герои Лермонтова, наделенные непреклонной волей и сильными страстями, стали символическим выражением неодолимого стремления человека к свободе.

Для широкого круга читателей.

Тематика:

ББК:

УДК:

ОКСО:

- ВО - Бакалавриат

- 44.03.01: Педагогическое образование

- 45.03.01: Филология

- 45.03.02: Лингвистика

ГРНТИ:

Скопировать запись

Фрагмент текстового слоя документа размещен для индексирующих роботов

MIKHAIL LERMONTOV THE DEMON

УДК 372.8 ББК 81.2 Англ-93 Л49 ISBN 978-5-9925-1427-8 Лермонтов, Михаил Юрьевич. Л49 Демон : книга для чтения на английском языке / М. Ю. Лермонтов. — [пер. с рус. Ирины Железновой, Аврил Пайман, Юджина М. Кайдена]. — СанктПетербург : КАРО, 2020. — 192 с. — (Русская классическая литература на иностранных языках). ISBN 978-5-9925-1427-8. Предлагаем вниманию читателей сборник поэтических произведений Михаила Юрьевича Лермонтова (1814–1841) в переводе на английский язык. В книгу вошли знаменитые поэмы «Демон» (1838), «Мцыри»(1839), «Песня про царя Ивана Васильевича, молодого опричника и удалого купца Калашникова» (1837) и избранные стихотворения 1831–1841 годов. Романтические герои Лермонтова, наделенные непреклонной волей и сильными страстями, стали символическим выражением неодолимого стремления человека к свободе. Для широкого круга читателей. УДК 372.8 ББК 81.2 Англ-93 © КАРО, 2019 Все права защищены

CONTENTS M. Y. Lermontov An article by Moissaye J. Olgin ......................................6 The Demon Translated by Avril Pyman ..........................................17 Mtsyri Translated by Irina Zheleznova ..................................69 The Lay of Tsar Ivan Vassilyevich, His Young Oprichnik and the Stouthearted Merchant Kalashnikov Translated by Irina Zheleznova .............................. 103 POEMS ............................................................................. 127 The Аngel Translated by Avril Pyman ....................................... 129 Ballad Translated by Avril Pyman ....................................... 130 The Сhains of Mountains Blue I Love... Translated by Irina Zheleznova .............................. 132 To*** Translated by Avril Pyman ....................................... 134 The Reed Translated by Irina Zheleznova .............................. 136 The Sail Translated by Irina Zheleznova .............................. 138

Not Byron — of a Different Kind… Translated by Avril Pyman ....................................... 139 The Mermaid Translated by Irina Zheleznova .............................. 140 On the Death of the Poet Translated by Avril Pyman ....................................... 142 Borodino Translated by Eugene M. Kayden ........................... 146 The Dagger Translated by Eugene M. Kayden ........................... 151 The Captive Translated by Irina Zheleznova .............................. 152 When Comes a Gentle Breeze… Translated by Irina Zheleznova .............................. 154 Though We Have Parted, on My Breast… Translated by Avril Pyman ....................................... 155 Pray, Laugh Not at a Gloom of Dark Foreboding Born… Translated by Irina Zheleznova ............... 156 Meditation Translated by Avril Pyman ....................................... 157 The Poet Translated by Avril Pyman ....................................... 160 Three Palms Translated by Irina Zheleznova .............................. 163 How Frequently Amidst the Many-Coloured Crowd... Translated by Avril Pyman ..................... 167 A Cossack Lullaby Translated by Irina Zheleznova .............................. 170

Because Translated by Avril Pyman ....................................... 173 Such Emptiness, Heartache Translated by Avril Pyman ....................................... 174 To A. O. Smirnova Translated by Irina Zheleznova .............................. 175 To a Child Translated by Irina Zheleznova .............................. 176 The Captive Knight Translated by Eugene M. Kayden ........................... 178 Farewell to Russia Translated by Eugene M. Kayden ........................... 179 Mountain Heights Translated by Eugene M. Kayden ........................... 180 Clouds Translated by Avril Pyman ....................................... 181 The Dream Translated by Irina Zheleznova .............................. 182 No, Not on You My Passion’s Bent… Translated by Avril Pyman ....................................... 184 The Cross Atop a Cliff Translated by Irina Zheleznova .............................. 185 Lone’s the Mist-Cloaked Road Before Me Lying… Translated by Irina Zheleznova ............................. 186 The Sea Princess Translated by Irina Zheleznova .............................. 188 The Cliff Translated by Irina Zheleznova .............................. 191

When we think of Lermontov, we see in our minds a huge mountain-peak somewhere in the heart of the Caucasus. Eternal silence reigns in its clefts and gorges. Its mass of ice and stone looks a picture of gloomy solitude. It seems to be indifferent to the turmoil of life. Still, there is boiling lava deep in its heart. Time and again it shakes from the fury of compressed inner forces. On its bare stony body little trees with lacy foliage climb higher and higher; and when the world is in bloom, winds laden with fragrance blow on its ragged brow, bringing the lure of distant lands. Such is the poet Lermontov. This is, perhaps, why he loved the Caucasus all his life. He is the most tragic of the Russian poets. From his very boyhood he was full of disdain for humanity, M. Y. LERMONTOV (1814–1841)

M. Y. Lermontov 7 whose life he thought shallow, empty, and ugly; at the same time, he was irresistibly attracted by this very meaningless life. He cherished the ideal of a demon, a proud, lonely, and powerful superhuman creature challenging peaceful virtues and conventional happiness; at the same time he was fiercely craving for mortal love and sunlit human happiness, the absence of which filled his heart with pain. He had a cool and strong intellect, a power of analysis and criticism which revealed the futility of endeavor in this world and dictated an attitude of bored aloofness; at the same time he was torn by mad passions prompting him to the most unreasonable actions. He was inclined to protest, to repudiate, to curse, and almost without noticing he drifted into a prayer or saw the vision of an angel singing his quiet song over “a world of grief and tears.” Altogether he is a profoundly unhappy nature, just the reverse of his older brother Pushkin. If Pushkin is primarily the poet of the Russian soul and Russian nature, Lermontov is the first of the great Russian poets of the spirit. And if Pushkin is fundamentally national, acquiring international significance through his closeness to his native land, Lermontov is of universal value in himself as expressing those doubts and moods and gropings which are common to all cultured men. This did not

M. Y. Lermontov prevent him from being a genuine Russian poet. One is even justified in looking for a connection between his dark rebellious moods and the dark conditions of the society in which he lived. Lermontov is a self-centered poet. “The most characteristic feature of Lermontov’s genius,” Vladimir Solovyov1 says, “is a terrific intensity of thought concentrated on himself, on his ego, a terrific power of personal feeling.” This, however, is no self-centeredness. Lermontov seeks refuge within himself because he finds no values in the ephemeral existence of the world. He sinks into brooding moods not because he finds in them satisfaction, but because life does not quell his thirst for harmony and truth. He is at war with society, with humanity, with the universe. He is at war even with God in the name of some great unearthly beauty which only at rare moments gives to his soul her luminous forebodings. If Pushkin is the poet of all the people, Lermontov is the poet of the thinking elements in it. As such he played a colossal rôle in the spiritual history of his country. Generation after generation learned from him to hate the sluggishness of Russian life and the convention of every life, to repudiate compromises, 1 Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov (1853–1900) — a Russian philosopher, theologian, poet, pamphleteer and literary critic. — Ed.

M. Y. Lermontov 9 to understand the longing of the soul for things nonexistent, and to cherish freedom in the broad sense of the word. Lermontov’s form is in full accord with his moods, varying from the most exquisite tenderness to “verses coined of iron, dipped in poignancy and gall,” from slow, thoughtful, and melancholy lines to volcanic outbursts of fury. In expressing delicate shades of emotions and in dignified refinement Lermontov is, perhaps, even superior to Pushkin. There is more of the elusive quality in his poems, that which cannot be expressed in definite words. Horrified by the triviality of life, by its corruption and helplessness, Lermontov sounded the motive of indignation. This indignation, so rare in Russia, utterly alien to Pushkin, timidly sounding in the work of Tchatzky1, unknown to Gogol, was something new and unheard of. Through Lermontov’s indignation, the Russian citizen for the first time became aware of himself as a real human being. The feeling of human dignity was stronger in Lermontov than all other feelings. It sometimes assumed unhealthy proportions, it led him to satanical pride, to contempt for all his surroundings. And in the name of this human dignity, 1 Tchatzky (Chatsky) is the main character of the comedy “Woe from Wit” by A. Griboedov. — Ed.

M. Y. Lermontov unrecognized and downtrodden, he raised the voice of indignation. It appeared to him that not only society, those hangmen of freedom and genius, but also the Deity that gave him life, are making attempts on his inalienable rights as a man and are preventing him from living a full, eternal life which alone was of value to him. He saw no prospect of eternal life, no fullness of existence, no love without betrayal, no passion without satiety, and he did not wish to agree to less, as a deposed ruler does not wish to receive donations from the hand of the victor. . . . Lermontov is a religious nature, but his religion is primarily a groping, an indefinite, hazy admittance of life’s tragic mystery. Evg. Solovyov (Andreyevitch)1 Lermontov introduced into literature the struggle against philistinism. Not, perhaps, till the end of the nineteenth century did philistinism meet a more ruthless, merciless foe. His aversion to philistinism is the key to his entire conception of life. His hatred for everything ordinary led him to his outspoken individualism and brought him near to that real romanticism which was unknown in Russia before him. It also 1 Evgeniy Andreyevitch Solovyov (1866–1905) — a Russian literary critic, literary historian and writer. — Ed.