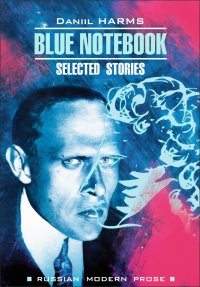

Голубая тетрадь

Книга для чтения на английском языке

Покупка

Тематика:

Английский язык

Издательство:

КАРО

Автор:

Хармс Даниил Иванович

Год издания: 2020

Кол-во страниц: 224

Возрастное ограничение: 12+

Дополнительно

Вид издания:

Художественная литература

Уровень образования:

Дополнительное образование

ISBN: 978-5-9925-1420-9

Артикул: 749949.02.99

Предлагаем вниманию читателя произведения Даниила Хармса (Даниила Ивановича Ювачева) (1905-1942), одного из основателей авангардной поэтической и художественной группы «Объединение реального искусства» (ОБЭРИУ). Противоречивый, иррациональный, настроенный революционно против всего привычного, пресного и скучного, Хармс увлекает читателя своим необычным стилем и интригующими сюжетами. Если вчитаться в произведения Хармса, то во всем, что он писал, обнаруживается отчаяние автора по поводу обесчеловечивания, господства лжи и пустоты в буднях коммунистической уравниловки. В августе 1941 года Даниил Иванович был арестован, помещен в психиатрическую больницу и умер в феврале 1942 года. Абсурдистское творчество Даниила Хармса официально признали в СССР лишь в 80-х годах прошлого века.

Произведения переведены на английский язык и будут интересны широкому кругу читателей.

Тематика:

ББК:

УДК:

ОКСО:

- ВО - Бакалавриат

- 44.03.01: Педагогическое образование

- 45.03.01: Филология

- 45.03.02: Лингвистика

ГРНТИ:

Скопировать запись

Фрагмент текстового слоя документа размещен для индексирующих роботов

daniil harms BLUE NOTEBOOK КАРО Санкт-Петербург

УДК 372.8

ББК 81.2 Англ-93

X21

Хармс, Даниил.

X21 Голубая тетрадь : книга для чтения на английском языке / Д. Хармс. — Санкт-Петербург : КАРО, 2020. — 224 с. — (Современная русская проза).

ISBN 978-5-9925-1420-9.

Предлагаем вниманию читателя произведения Даниила Хармса (Даниила Ивановича Ювачева) (1905-1942), одного из основателей авангардной поэтической и художественной группы «Объединение реального искусства» (ОБЭРИУ).

Противоречивый, иррациональный, настроенный революционно против всего привычного, пресного и скучного, Хармс увлекает читателя своим необычным стилем и интригующими сюжетами. Если вчитаться в произведения Хармса, то во всем, что он писал, обнаруживается отчаяние автора по поводу обесчеловечивания, господства лжи и пустоты в буднях коммунистической уравниловки.

В августе 1941 года Даниил Иванович был арестован, помещен в психиатрическую больницу и умер в феврале 1942 года.

Абсурдистское творчество Даниила Хармса официально признали в СССР лишь в 80-х годах прошлого века.

Произведения переведены на английский язык и будут интересны широкому кругу читателей.

УДК 372.8

ББК 81.2 Англ-93

ISBN 978-5-9925-1420-9

© КАРО, 2019

KALINDOV

Kalindov was standing on tiptoe and peering at me straight in the face. I found this unpleasant. I turned aside but Kalindov ran round me and was again peering at me straight in the face. I tried shielding myself from Kalindov with a newspaper. But Kalindov outwitted me: he set my newspaper alight and, when it flared up, I dropped it on the floor and Kalindov again began peering at me straight in my face. Slowly retreating, I repaired behind the cupboard and there, for a few moments, I enjoyed a break from the importunate stares of Kalindov. But my break was not prolonged: Kalindov crawled up to the cupboard on all fours and peered up at me from below. My patience ran out; I screwed up my eyes and booted Kalindov in the face.

When I opened my eyes, Kalindov was standing in front of me, his face bloodied and mouth lacerated, peering at me straight in the face as before.

3

SYMPHONY NO. 2

Anton Mikhailovich spat, said “yuck”, spat again, said “yuck” again, spat again, said “yuck” again and left. To Hell with him. Instead, let me tell about Ilya Pavlovich.

Ilya Pavlovich was born in 1893 in Constantinople. When he was still a boy, they moved to St. Petersburg, and there he graduated from the German School on Kirochnaya Street. Then he worked in some shop; then he did something else; and when the Revolution began, he emigrated. Well, to Hell with him. Instead, let me tell about Anna Ignatievna.

But it is not so easy to tell about Anna Ignatievna. Firstly, I know almost nothing about her, and secondly, I have just fallen of my chair, and have forgotten what I was about to say. So let me instead tell about myself.

I am tall, fairly intelligent; I dress prudently and tastefully; I don’t drink, I don’t bet on horses, but I like ladies. And ladies don’t mind me. They like when I go

4

out with them. Serafima Izmaylovna have invited me home several times, and Zinaida Yakovlevna also said that she was always glad to see me.

But I was involved in a funny incident with Marina Petrovna, which I would like to tell about. A quite ordinary thing, but rather amusing. Because of me, Marina Petrovna lost all her hair — got bald like a baby’s bottom. It happened like this: once I went over to visit Marina Petrovna, and bang! she lost all her hair. And that was that.

5

FIVE UNFINISHED NARRATIVES

Dear Yakov Semyonovich,

1. A certain man, having taken a run, struck his head against a smithy with such force that the blacksmith put aside the sledge-hammer which he was holding, took off his leather apron and, having smoothed his hair with his palm, went out on to the street to see what had happened.

2. Then the smith spotted the man sitting on the ground. The man was sitting on the ground and holding his head.

3. — What happened? — asked the smith. — Ooh! — said the man.

4. The smith went a bit closer to the man.

5. We discontinue the narrative about the smith and the unknown man and begin a new narrative about four friends and a harem.

6. Once upon a time there were four harem fanatics. They considered it rather pleasant to have

6

eight women at a time each. They would gather of an evening and debate harem life. They drank wine; they drank themselves blind drunk; they collapsed under the table; they puked up. It was disgusting to look at them. They bit each other on the leg. They bandied obscenities at each other. They crawled about on their bellies.

7. We discontinue the story about them and begin a new story about beer.

8. There was a barrel of beer and next to it sat a philosopher who contended: — This barrel is full of beer; the beer is fermenting and strengthening. And I in my mind ferment along the starry summits and strengthen my spirit. Beer is a drink flowing in space; I also am a drink, flowing in time.

9. When beer is enclosed in a barrel, it has nowhere to flow. Time will stop and I will stand up.

10. But if time does not stop, then my flow is immutable.

11. No, it’s better to let the beer flow freely, for it’s contrary to the laws of nature for it to stand still. — And with these words the philosopher turned on the tap in the barrel and the beer poured out over the floor.

12. We have related enough about beer; now we shall relate about a drum.

13. A philosopher beat a drum and shouted: — I am making a philosophical noise! This noise is of

7

no use to anyone, it even annoys everyone. But if it annoys everyone, that means it is not of this world. And if it’s not of this world, then it’s from another world. And if it is from another world, then I shall keep making it.

14. The philosopher made his noise for a long time. But we shall leave this noisy story and turn to the following quiet story about trees.

15. A philosopher went for a walk under some trees and remained silent, because inspiration had deserted him.

8

BLUE NOTEBOOK NO. 10

Once there was a redheaded man without eyes and without ears. He had no hair either, so that he was a redhead was just something they said.

He could not speak, for he had no mouth. He had no nose either.

He didn’t even have arms or legs. He had no stomach either, and he had no back, and he had no spine, and no intestines of any kind. He didn’t have anything at all. So it is hard to understand whom we are really talking about.

So it is probably best not to talk about him any more.

9

KOKA BRIANSKY Act I Koka Briansky: I’m getting married today. Mother: What? Koka Briansky: I’m getting married today! Mother: What? Koka Briansky: I said I’m getting married today. Mother: What did you say? Koka Briansky: To-day — ma-rried! Mother: Ma? What’s ma? Koka Briansky: Ma-rri-age! Mother: Idge? What’s this idge? Koka Briansky: Not idge, but ma-rri-age! Mother: What do you mean, not idge? Koka Briansky: Yes, not idge, that’s all! Mother: What? Koka Briansky: Yes, not idge. Do you understand?! Not idge! 10