Маленькая принцесса

Покупка

Тематика:

Английский язык

Издательство:

КАРО

Автор:

Бернетт Фрэнсис Ходжсон

Коммент., словарь:

Алексеенко Д. В.

Год издания: 2016

Кол-во страниц: 256

Возрастное ограничение: 12+

Дополнительно

Вид издания:

Художественная литература

Уровень образования:

ВО - Бакалавриат

ISBN: 978-5-9925-1123-9

Артикул: 642676.02.99

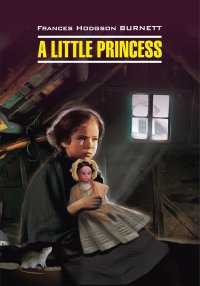

«Маленькая принцесса» — роман английской писательницы Френсис Бёрнетт, написанный в 1905 году, в наше время входит в топ-100 детских книг, рекомендованных Национальной Ассоциацией Образования Америки для детского чтения. Главная героиня романа, Сара Кру, переживет множество невзгод, но, благодаря пытливому уму и любознательности, останется настоящей принцессой в любой жизненной ситуации и в конце концов станет счастливой. Книга позволит юным читателям задуматься о том, что такое дружба и честность.

Неадаптированный текст на языке оригинала снабжен постраничными комментариями и словарем.

Тематика:

ББК:

УДК:

ОКСО:

- ВО - Бакалавриат

- 44.03.01: Педагогическое образование

- 45.03.01: Филология

- 45.03.02: Лингвистика

- 45.03.99: Литературные произведения

ГРНТИ:

Скопировать запись

Фрагмент текстового слоя документа размещен для индексирующих роботов

УДК 372.8 ББК 81.2 Англ-93 Б51 ISBN 978-5-9925-1123-9 Бёрнетт, Фрэнсис Ходжсон. Б51 Маленькая принцесса : книга для чтения на английском языке. — Санкт-Петербург : КАРО, 2016. — 256 с. — (Classical Literature). ISBN 978-5-9925-1123-9. «Маленькая принцесса» — роман английской писательницы Френсис Бёрнетт, написанный в 1905 году, в наше время входит в топ-100 детских книг, рекомендованных Национальной Ассоциацией Образования Америки для детского чтения. Главная героиня романа, Сара Кру, переживет множество невзгод, но, благодаря пытливому уму и любознательности, останется настоящей принцессой в любой жизненной ситуации и в конце концов станет счастливой. Книга позволит юным читателям задуматься о том, что такое дружба и честность. Неадаптированный текст на языке оригинала снабжен постраничными комментариями и словарем. УДК 372.8 ББК 81.2 Англ-93 © КАРО, 2016 Оптовая торговля: Книги издательства «КАРО» можно приобрести: Интернетмагазины: в СанктПетербурге: ул. Бронницкая, 44. тел./факс: (812) 5759439, 3208479 еmail: karopiter@mail.ru, karo@peterstar.ru в Москве: ул. Стахановская, д. 24. тел./факс: (499) 1715322, 1740964 Почтовый адрес: 111538, г. Москва, а/я 7, еmail: moscow@karo.net.ru, karo.moscow@gmail.com WWW.BOOKSTREET.RU WWW.LABIRINT.RU WWW.MURAVEISHOP.RU WWW.MYSHOP.RU WWW.OZON.RU

1 Sara Once on a dark winter’s day, when the yellow fog hung so thick and heavy in the streets of London that the lamps were lighted and the shop windows blazed with gas as they do at night, an odd-looking little girl sat in a cab1 with her father and was driven rather slowly through the big thoroughfares2. She sat with her feet tucked under her, and leaned against her father, who held her in his arm, as she stared out of the window at the passing people with a queer oldfashioned thoughtfulness in her big eyes3. She was such a little girl that one did not expect to see such a look on her small face. It would have been an old look for a child of twelve4, and Sara Crewe was only seven. Th e fact was, however, that she was always dreaming and thinking odd things and could not herself remember any time when she had not been thinking things about grownup people and the world they belonged to. She felt as if she had lived a long, long time. 1 cab — наемный экипаж 2 thoroughfares — оживленные улицы 3 with a queer old-fashioned thoughtfulness in her big eyes — со странной, старомодной задумчивостью в глазах 4 It would have been an old look for a child of twelve — Такой взгляд был бы странным даже для двенадцатилетнего ребенка

At this moment she was remembering the voyage she had just made from Bombay1 with her father, Captain Crewe. She was thinking of the big ship, of the Lascars2 pas sing silent ly to and fro on it, of the children playing about on the hot deck, and of some young offi cers’ wives who used to try to make her talk to them and laugh at the things she said. Principally, she was thinking of what a queer thing it was that at one time one was in India in the blazing sun, and then in the middle of the ocean, and then driving in a strange vehicle through strange streets where the day was as dark as the night. She found this so puzzling that she moved closer to her father. “Papa,” she said in a low, mysterious little voice which was almost a whisper, “papa.” “What is it, darling?” Captain Crewe answered, holding her closer and looking down into her face. “What is Sara thinking of?” “Is this the place?” Sara whispered, cuddling still closer to him. “Is it, papa?” “Yes, little Sara, it is. We have reached it at last.” And though she was only seven years old, she knew that he felt sad when he said it. It seemed to her many years since he had begun to prepare her mind for “the place,” as she always called it. Her mother had died when she was born, so she had never known or missed her. Her young, handsome, rich, petting father seemed to be the only relation she had in the world. Th ey had always played together and been fond of each other. She only knew he was rich because she had heard 1 Bombay — Бомбей. Такое название до 1995 года носил индийский город Мумбаи 2 Lascars — (вост.-инд.) моряки

people say so when they thought she was not listening, and she had also heard them say that when she grew up she would be rich, too. She did not know all that being rich meant. She had always lived in a beautiful bungalow, and had been used to seeing many servants who made salaams1 to her and called her “Missee Sahib2,” and gave her her own way3 in everything. She had had toys and pets and an ayah4 who worshipped her, and she had gradually learned that people who were rich had these things. Th at, however, was all she knew about it. During her short life only one thing had troubled her, and that thing was “the place” she was to be taken to some day. Th e climate of India was very bad for children, and as soon as possible they were sent away from it — generally to England and to school. She had seen other children go away, and had heard their fathers and mothers talk about the letters they received from them. She had known that she would be obliged5 to go also, and though sometimes her father’s stories of the voyage and the new country had attracted her, she had been troubled by the thought that he could not stay with her. “Couldn’t you go to that place with me, papa?” she had asked when she was fi ve years old. “Couldn’t you go to school, too? I would help you with your lessons.” “But you will not have to stay for a very long time, little Sara,” he had always said. “You will go to a nice house where 1 to make salaams — кланяться (обычно является актом выражения почтения и подчинения в исламских культурах) 2 Sahib — господин, госпожа (обращение в Индии) 3 to give someone his / her own way — позволять вести себя как хочется 4 ayah — няня, служанка в Индии 5 to be obliged — быть обязанной

there will be a lot of little girls, and you will play together, and I will send you plenty of books, and you will grow so fast that it will seem scarcely a year1 before you are big enough and clever enough to come back and take care of papa.” She had liked to think of that. To keep the house for her father; to ride with him, and sit at the head of his table when he had dinner parties; to talk to him and read his books — that would be what she would like most in the world, and if one must go away to “the place” in England to attain it, she must make up her mind2 to go. She did not care very much for other little girls, but if she had plenty of books she could console herself. She liked books more than anything else, and was, in fact, always inventing stories of beautiful things and telling them to herself. Sometimes she had told them to her father, and he had liked them as much as she did. “Well, papa,” she said soft ly, “if we are here I suppose we must be resigned3.” He laughed at her old-fashioned speech and kissed her. He was really not at all resigned himself, though he knew he must keep that a secret. His quaint little Sara had been a great companion to him, and he felt he should be a lonely fellow when, on his return to India, he went into his bungalow knowing he need not expect to see the small fi gure in its white frock come forward to meet him. So he held her very closely in his arms as the cab rolled into the big, dull square in which stood the house which was their destination. 1 it will seem scarcely a year — покажется, что и года не прошло 2 to make up someone’s mind — решать 3 to be resigned — быть готовым

It was a big, dull, brick house, exactly like all the others in its row, but that on the front door there shone a brass plate on which was engraved in black letters: MISS MINCHIN, Select Seminary for Young Ladies. “Here we are, Sara,” said Captain Crewe, making his voice sound as cheerful as possible. Th en he lift ed her out of the cab and they mounted the steps1 and rang the bell. Sara oft en thought aft erward that the house was somehow exactly like Miss Minchin. It was respectable and well furnished, but everything in it was ugly; and the very armchairs2 seemed to have hard bones in them. In the hall everything was hard and polished — even the red cheeks of the moon face on the tall clock in the corner had a severe varnished look. Th e drawing room3 into which they were ushered was covered by a carpet with a square pattern upon it, the chairs were square, and a heavy marble timepiece stood upon the heavy marble mantel4. As she sat down in one of the stiff mahogany chairs, Sara cast one of her quick looks5 about her. “I don’t like it, papa,” she said. “But then I dare say6 soldiers — even brave ones — don’t really LIKE going into battle.” 1 to mount the steps — взобраться по ступенькам 2 the very armchairs — даже кресла 3 drawing room — гостиная 4 a heavy marble timepiece stood upon the heavy marble mantel — тяжелые мраморные часы стояли на массивной мраморной каминной полке 5 to cast a look — бросить взгляд 6 I dare say — осмелюсь сказать

Captain Crewe laughed outright at this. He was young and full of fun, and he never tired of hearing Sara’s queer speeches. “Oh, little Sara,” he said. “What shall I do when I have no one to say solemn things to me? No one else is as solemn as you are.” “But why do solemn things make you laugh so?” inquired Sara. “Because you are such fun when you say them,” he answered, laughing still more. And then suddenly he swept her into his arms and kissed her very hard, stopping laughing all at once and looking almost as if tears had come into his eyes. It was just then that Miss Minchin entered the room. She was very like her house, Sara felt: tall and dull, and respectable and ugly. She had large, cold, fi shy eyes, and a large, cold, fi shy smile. It spread itself into a very large smile1 when she saw Sara and Captain Crewe. She had heard a great many desirable things of the young soldier from the lady who had recommended her school to him. Among other things, she had heard that he was a rich father who was willing to spend a great deal of money2 on his little daughter. “It will be a great privilege to have charge3 of such a beautiful and promising child, Captain Crewe,” she said, taking Sara’s hand and stroking it. “Lady Meredith has told me of her unusual cleverness. A clever child is a great treasure in an establishment like mine.” 1 It spread itself into a very large smile — Губы растянулись в очень широкой улыбке 2 a great deal of money — изрядное количество денег 3 to have charge — присматривать

Sara stood quietly, with her eyes fixed upon Miss Minchin’s face. She was thinking something odd, as usual. “Why does she say I am a beautiful child?” she was thinking. “I am not beautiful at all. Colonel Grange’s little girl, Isobel, is beautiful. She has dimples and rose-colored cheeks, and long hair the color of gold. I have short black hair and green eyes; besides which, I am a thin child and not fair in the least1. I am one of the ugliest children I ever saw. She is beginning by telling a story.2” She was mistaken, however, in thinking she was an ugly child. She was not in the least like Isobel Grange, who had been the beauty of the regiment3, but she had an odd charm of her own. She was a slim, supple creature, rather tall for her age, and had an intense, attractive little face. Her hair was heavy and quite black and only curled at the tips; her eyes were greenish gray4, it is true, but they were big, wonderful eyes with long, black lashes, and though she herself did not like the color of them, many other people did. Still she was very fi rm in her belief that she was an ugly little girl, and she was not at all elated by Miss Minchin’s fl attery. “I should be telling a story if I said she was beautiful,” she thought; “and I should know I was telling a story. I believe I am as ugly as she is — in my way. What did she say that for?” 1 not fair at the least — кожа у меня не такая уж светлая 2 She is beginning by telling a story. — Она начинает с того, что говорит неправду. 3 who had been a beauty of regiment — красота которой была признана всем полком 4 her eyes were greenish gray — ее глаза были зеленоватосерыми

Aft er she had known Miss Minchin longer she learned why she had said it. She discovered that she said the same thing to each papa and mamma who brought a child to her school. Sara stood near her father and listened while he and Miss Minchin talked. She had been brought to the seminary because Lady Meredith’s two little girls had been educated there, and Captain Crewe had a great respect for Lady Meredith’s experience. Sara was to be what was known as “a parlor boarder”1, and she was to enjoy even greater privileges than parlor boarders usually did. She was to have a pretty bedroom and sitting room of her own; she was to have a pony and a carriage, and a maid to take the place of the ayah who had been her nurse in India. “I am not in the least anxious about her education2,” Captain Crewe said, with his gay laugh, as he held Sara’s hand and patted it. “Th e diffi culty will be to keep her from learning too fast and too much. She is always sitting with her little nose burrowing into books. She doesn’t read them, Miss Minchin; she gobbles them up as if she were a little wolf instead of a little girl. She is always starving for new books to gobble, and she wants grown-up books — great, big, fat ones — French and German as well as English — history and biography and poets, and all sorts of things. Drag her away from her books when she reads too much. Make her ride her pony in the Row or go out and buy a new doll. She ought to play more with dolls.” 1 a parlor boarder — школьник-пансионер (обычно ребенок богатых родителей, отданный под личный присмотр директора школы и пользующийся такими привилегиями, как собственная комната, возможность иметь прислугу и т. д.) 2 I am not in the least anxious about her education — Я совершенно не беспокоюсь из-за ее образования